Justin Bua: Raising the Profile of Street Art

Street art: It’s not just for the streets anymore. Not only has the influence of graffiti infiltrated high-end art shows and galleries around the civilized and uncivilized worlds alike, it’s also on prime time—in the form of the reality competition series Street Art Throwdown, airing on Oxygen Tuesday nights.

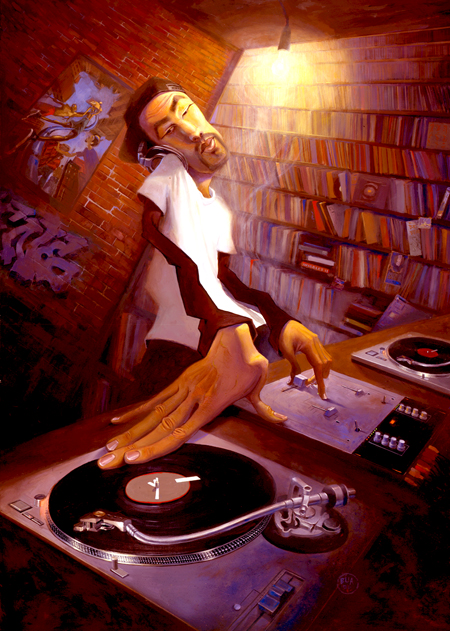

At the helm of the show is one of the biggest names in the street art world: Justin Bua, known simply as “Bua,” whose work has been splashed across many a cityscape wall, canvas and art book. In the process, he has helped elevate the art of the streets.

“We had addicts, drug dealers, murderers, criminals, pimps, hustlers. But we also had the spark of hip-hop. We had the spark of something that was a creative collective, that energy in the street…”

His warped, Dali-esque interpretations of urban scenarios and obsessions have had as much to do with raising the profile of street art as the graffiti greats themselves. We caught up with the man at his Echo Park workspace to discover more about his inspirations and motivation for taking something with such underground roots into the mainstream.

You grew up in a special time in New York. Describe the scene in which graffiti was born.

My childhood growing up in New York City was absolutely insane. I lived next to two welfare hotels on my block. I had 200 in my neighborhood. New York City was chaos. It was like the Wild West; it was Dodge City. We had addicts, drug dealers, murderers, criminals, pimps, hustlers—that was my surrounding. But we also had the spark of hip-hop. We had the spark of something that was a creative collective, that energy in the street we were able to plug into. Having a block party, we would plug into the lamppost and suck the energy off the street because the cops weren’t really watching. We had all this angst and all this energy and desire to be creative, and hip-hop came from that really raw sense of change.

What were the influences that pushed you to paint?

My mom and my grandfather were both painters, so to me, I had a classical world in my house. But on the streets, we had great street art. We had Zephyr, we had Dondi, we had Futura 2000, we had all of these great icons, and I was infused with all of those steel giant worms pulling into the stations and seeing that painting on the actual trains. Plus, I would go to the Freedom Tunnel and the Ghost Yards and see all this graffiti. So it was an amalgamation of the classical work in my house and the art in the street that really was absorbed by my brain.

How did your fine arts background give rise to work that evokes such a B-boy vibe?

My style really comes from B-boying—from the energy and rhythms of popping, you know? It’s got this angularity, but it’s also got this flow to it because that was the world that I was from, and we saw things from a distorted lens. We saw things like crazy city kids. It’s kind of like a Wu-Tang song come to life visually. So the way that I bust is very crazy—but at the same time classical, because I’ve trained a lot. I went to the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts, and I studied classical figure drawing and painting. Then I went to Art Center College in Pasadena; I have a BFA in painting. So my world is insane, and it’s distorted, and it’s wild. But it’s always been that way, ever since I was a kid until right now. The style has just evolved.

When did the passion turn into a profession?

I started doing slick-bottom skateboards for the skating industry back in the days. The kids really liked my work, and I started doing posters as fine art posters. And my DJ paintings literally sold like 10,000 overnight. I realized, like, “Wow, I could do this for real life. People are really loving my stuff.” I was just doing it because I loved doing it. And everyone around was like, “You shouldn’t do that. No one is into DJs.” I was like, “I don’t really care. This is my world; I know DJs. This is my entire environment—MCs and B-boys.” And that’s what I painted. I painted what I knew. I painted the iconic characters of the hip-hop scene, so people could relate to that.

When did street art become fine art?

Basically, street art was getting into galleries back in the days. You know Fab 5 Freddy, Leak and Tracy 168—they were actually in galleries in New York City. But the massive explosion has just happened recently, because street art is so authentic… I was writing on the street and in the black books in the ‘80s for nothing more than the love. I was never getting paid for it.

“The first thing that people cut are art programs. People need to see art. Art is important.”

I assume that has changed, and you’re making quite a career off an art form associated with being antiestablishment.

Now street art has just exploded on an international platform. I mean, it’s everywhere; it’s omnipresent. It’s outside the walls, it’s inside the galleries. You know, when I was a kid I was doing Black Book, piecing in my neighborhood getting up on the trains. But now I paint on an easel. And Street Art Throwdown is an amazing opportunity to get these kids’ work on a world platform so the world can see it, because it’s about time. The first thing that people cut are art programs. People need to see art. Art is important. And Street Art Throwdownallows people to see artists—not just the contestants, but judges as well. Street art is probably the most important artist movement ever.

How long will street art/graffiti be cool? It just doesn’t seem to go out of style.

It’s the longest movement ever. It’s been around since the ‘60s. It’s still growing, it’s still getting bigger. It’s lasted longer that deism, neoclassicism, impressionism. I anticipate it’s going to be around forever. And technically in street art, you think of writings on the walls, you think of cave paintings in Belasco, France, you think of the paintings on the catacombs in Rome. Painting outside [and] interacting with public space has been going on since the beginning of time. It’s just getting way more out there into the minds and consciousness of everybody.

You’re the host and director of Street Art Throwdown. What went into getting a show like this on primetime?

I created the show with my partner, Darren Chavez. I really have always mentored kids, [and] I’ve taught all over. I taught at USC for 10 years, and I was always really into mentoring and making a better situation for kids—giving them the skill sets that they need. So you know Street Art Throwdown is the perfect vehicle for me. Not only am I the host and the judge, but I’m able to mentor them and take them to another level.

I’d imagine getting a bunch of stuffy studio execs to green-light a show that centers on graffiti was quite a mission.

Yeah, getting on the air was incredibly difficult; but Oxygen gave us the opportunity, and that’s really a miracle. If you know anything about TV, you know how hard it is to get a show. I think that for the first time ever, the world is ready for this. The world is ready to see art out there on such a global level. Now is the time.