Dancing in the Dark

This home of dreams is ghostly tonight, like Downtown Los Angeles seemed for so many years. On a late March evening this past winter, the birthplace of Insomniac’s Nocturnal Wonderland—at 2708 East Cesar E. Chavez Avenue—looks like an empty two-story mansion with boarded-up windows, red brick walls, and Spanish arches that hide deep rooms and long staircases within. The streets around it feel eerie, not a soul walking about.

“A lot of people at the time said it was a very bad idea to do a techno party, but that was the music I liked. I wanted to feel like a kid again.”

It was here, just east of the Los Angeles River in Boyle Heights—more than 20 years ago, on Saturday, February 11, 1995—that a line of ravers stretched around the block as bass throbbed from the inside. They were part of a new era, not just for Insomniac’s hometown, but for a movement reaching far outside its dusty, fractured concerns. You can almost see their afterimage.

“A concrete warehouse vibrates with each dropping beat,” a Net.Werk zine profile of Insomniac began, published a few months before the first Nocturnal. “The hard walls covered with visions of psychedelic dreams, an array of colors splashes against the wave of dancers in unison with the rumbling bass. Oversize, red and white hats bob up and down in this sea of sweat-soaked speaker stompers, whistles screech and voices scream in ecstasy of the heavy beat.”

The year prior, Pasquale Rotella had thrown a Friday night weekly called “Insomniac.” It was often touch and go. The map point—the first stop you’d have to hit to get the location of the party itself—was run off the front table of a coffee shop unaware of his underground operation. Locations were hard to secure and sometimes in rough neighborhoods.

From the start, his parties harkened to the good vibes of L.A.’s initial 1990–92 rave boom. For Rotella, the sound of those good vibes was “techno,” which at the time had come to mean a swaggering hybrid of every electronic dance style that came before it. It was synonymous with the West Coast’s biggest raves.

“A lot of people at the time said it was a very bad idea to do a techno party, but that was the music I liked,” Rotella told Net.Werk editor Lisa Pisa in that same October 1994 article, pointing to the more opiate flavors of dance that were splintering off into the L.A. after-hours scene. “The whole year when I would go out, there was nothing I would enjoy going to. I was sick of going out and not having as good a time as I used to in the scene. I wanted to feel like a kid again.”

Both nostalgic and futuristic, Nocturnal Wonderland was designed to open the door to a bright origin myth by looping back to rave’s genesis. For inspiration, he chose Lewis Carroll’s timeless books Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass.

“It was something I just naturally gravitated toward,” he says now. “I wanted people to go on an adventure when they came to my shows. It was perfectly fitting—going to find venues and warehouses and going into these worlds.”

Part fairy tale exuberance, part adult contemplation, Nocturnal Wonderland’s mission was to remind the rave scene of its prime directive: to bring people together on one dancefloor.

DJ Joel “Mojo” Semchuck, who played the first Nocturnal, remembers techno as highly eclectic music filled with a sharp attitude and heavy vibes in the low end. Some of its biggest signatures ranged from R&S’s rolling, elastic classic “Dominator” by Human Resource, to the black R&B soul of “Show Me Love” by Robin S., house rhythms bouncing through the octaves and her voice burning from the inside.

“Techno was a little bit higher energy,” says Mojo. “It had more breakbeats, more sirens and the ‘Dominator’-style, the really powerful synth stabs. When people think of techno, they think of Detroit, or they think breakbeat or proto-jungle, because all that stuff was mixed in together: Belgian techno and Dutch techno and Detroit techno and UK breakbeat techno. It was just a mishmash of styles, and even some house and acid house and trance-y stuff all mixed in together. That’s what made what we called ‘techno’ techno.”

“It was just a mishmash of styles, and even some house and acid house and trance-y stuff all mixed in together. That’s what made what we called ‘techno’ techno.”

Net.werk’s Pisa describes it today in more native terms: “L.A. had a very urban, almost heavy bass, hip-hop feel to it, with a little bit of G-funk in there. It just had a different feeling than the other cities that were putting out techno at the time.”

By the mid-‘90s, dance music was breaking up into segregated universes. Insomniac wanted to hold them together, while keeping the door open to newcomers. And the first Nocturnal Wonderland was Rotella’s biggest shot at pushing that frontier.

“It was kind of funny,” says Jason Blakemore, aka DJ Trance, who was an up-and-coming DJ from suburban Orange County. “Insomniac wanted to do an ‘old-school’ thing in 1995—go back to 1991, 1992—but it had only been a couple years since the rave explosion. It was going so fast back then.”

It may seem obvious now, but kids throwing underground parties in forgotten parts of L.A.—using pagers and first-generation mobile phones to do it—was like landing on Mars in 1991 or 1995.

“Nowadays, we take for granted all our technology resources,” says Jason Bentley, KCRW’s music director and a regular DJ at early Nocturnals. “Back then, it didn’t stop anybody. It was more of a challenge: voicemail lines, map points, crisscrossing Southern California. It was unbelievable. It’s like water. Water just finds its way. It will keep going around and carving its way to its ultimate destination. That was always part of the rave scene. It really needed to be an adventure, and it definitely was.”

“Nowadays, we take for granted all our technology resources,” says Jason Bentley, KCRW’s music director and a regular DJ at early Nocturnals. “Back then, it didn’t stop anybody. It was more of a challenge: voicemail lines, map points, crisscrossing Southern California. It was unbelievable. It’s like water. Water just finds its way. It will keep going around and carving its way to its ultimate destination. That was always part of the rave scene. It really needed to be an adventure, and it definitely was.”

“I was 19, going on 15,” laughs Rotella. “I was very young. I didn’t know who was going to show up or how many people. I could see nothing else but this party. Like, kill me if nobody shows up tonight. It was everything. If that event didn’t go on tonight, if it wasn’t good, my life was over. That’s how I felt.”

A review of the party in Net.werk puts about 1,500 ravers in Boyle Heights that night: “Following the voicemails, we parked at a Ralph’s and waited among about 500 people to board buses that took us to the location about two blocks away. Let off the bus, there was an even bigger line to get in. At around 3 a.m., capacity of about 1,000 was reached easily with over 500 kids trying to get in. Inside, the place was packed.”

Blakemore was on the bill for the main room, both to DJ and play live with local acid breaks producer Mike Knapp, aka Xpando. “I remember it being dark with red walls, going up the stairs, being sweaty, carrying my records, all the DJs being there waiting, stressed and being sweaty too,” Blakemore says. “I just jumped on. I don’t remember if I was even quite supposed to play right then.”

Like any rave, the music was loud, a mix of chaos and rhythmic order. “It was the Wild West out there,” recalls Mike Gutierrez, who owned the infamous Shredder sound company that worked Nocturnal that night. “The thing about the music, that bassline, I never felt like I had to get high. When I stood in front of the speakers and that sound moved me… it felt like you were swimming in an ocean, and the water was pushing you one way or the other. I could just close my eyes.”

Everyone’s retinas received waves of energy, too. Upstairs and downstairs, Rotella bathed every surface with blacklights, loops and lasers. “I used to have these lights called ‘oil wheels,’” he remembers. “They were these glass circles, with very thin, thin glass… When you turned it on, the wheel would spin, the oils would melt and the colors would mix. I had to hit the wall at the right angle and just make that wall melt.”

Aldo Bender, a surfer DJ known then for his progressive techno, was on the second floor with Blakemore. “I think that was the first event Pasquale had hired me,” he says. “It was hot. It was on one of the floors; once you were up there, big light productions, technicolor parade, projections everywhere. It was a good crowd with great energy.”

The energy that night was pulsing like the binary on/off switch of a city computer. While Blakemore and Xpando performed live as Rebirth, the power to their DAT (digital audio tape) machine kept going out. Panicked, Blakemore looked back many times and thought he saw Bender bobbing his chair back, bumping the power cord.

“I don’t remember who was playing…But everyone speaker humping made the second floor feel like we were gonna end up on the first floor.”

“Aldo Bender being back there, bumping the plug and it shutting off—we were playing a lot from a DAT, and I think maybe he was messing with us for relying on it,” Blakemore says with a laugh. “Or maybe it was just a mistake. You know how these things go. It probably wasn’t even him, but some other DJ.”

Despite the hiccups, one live track in particular captured the night: Rebirth’s “Pure.” As Blakemore recounts, the song was inspired by Scott Hardkiss’ “Raincry” as God Within. But Xpando and Blakemore’s take on that spiritualist sound was unique. It wobbles along to a rubbery bassline and hi-hats syncopating like flamenco castanets, a long magic-carpet ride for the dancefloor. But it’s the male vocals gasping in a kind of morning prayer that set “Pure” apart, rising for several bars without beats, giving dancers a dawn within.

“Xpando and Trance, they had just put out their Rebirth record, which was getting lots of play,” remember Pisa. “We were very proud of them, because they were local boys who had made this hit. And then seeing them live in the underground environment was pretty awesome.”

DJ R.A.W.—who records today as dubstep artist 6Blocc, and would go on to spearhead L.A.’s drum & bass scene—was also tearing it up that night.

“R.A.W. was such a skilled DJ,” says Jeff Adachi, aka DJ Simply Jeff. “He was able to take that same influence—scratching and cut & paste—and go nuts. When Raoul came on, he was just incredibly, technically good.”

“I don’t remember who was playing—probably R.A.W.,” says Arturo Cazares, a longtime raver who remembers one thing clearest about that night: “But everyone speaker humping made the second floor feel like we were gonna end up on the first floor.”

“It went off,” says Rotella. “It was a good feeling. But I was worried about the floor at one point. I never thought about that until all those people were there, and I was suddenly worried about it collapsing. It was just so crowded.”

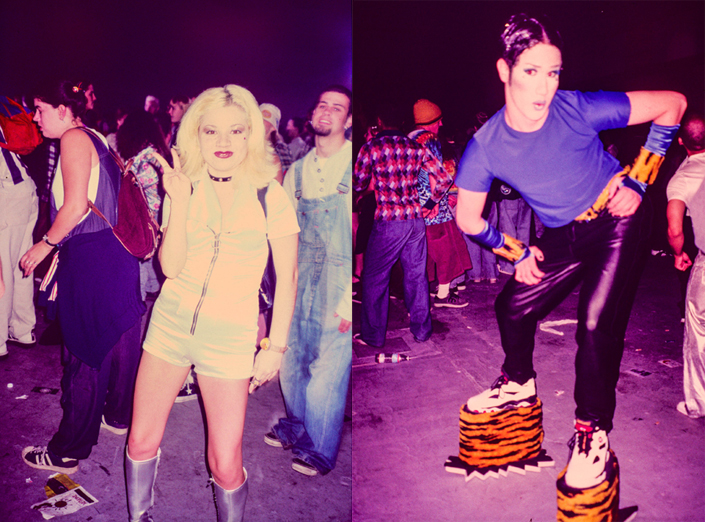

In its purest form, the rave scene was about freedom of thought—not just in the music, but in the way people moved and dressed. “It was all about how much imagination you could bring to the event,” says Bentley.

“There were a handful of people that were there that—still to this day—I have their faces etched into my brain, ‘till the day I die,” says Rotella. “There were these characters, and they made these events fun. I didn’t know their names, but they were something else.

“There was this guy—he wore a Domino’s Pizza shirt. I think he would literally get off work delivering pizza and rock his shirt, and that was his trademark. I don’t know if he really worked there, but that’s what I imagined.

“There were these other two guys that would wear giant overalls,” he says, recalling ravers like a DJ recalls records. “They would wear Cat in the Hat hats—one red and white, and one green and purple. They would always roll through together. You could never see their eyes; they’d always have their hats pulled really low, and they’d always be hanging out next to the speakers.

“And you had these two girls that were like the girl versions of them. They had the best style. They’d change it up and kind of match a little bit, with furry overalls and their hats pulled down. They had really white faces, like they were powdered, with bright red lipstick, and you couldn’t see their eyes. They were really mysterious looking.

“There was a dude that always had a cane,” he says. “He’d be in the dance circles. There was a guy that had the hugest hat ever. You could see him in the room no matter where you were standing.”

“You’d get people from all over,” says Pisa. “All the San Fernando Valley kids ended up knowing each other; you’d meet up in Los Angeles. And then you’d get the East L.A. kids. You’d get the South L.A. kids. We all came together from different parts of Los Angeles to party at these events, and I loved that it had that diversity. I would have never gone to East L.A. if it weren’t for undergrounds. I would not really know much about it, or go to South Central. I would never get to experience these types of neighborhoods.”

“You’d get people from all over,” says Pisa. “All the San Fernando Valley kids ended up knowing each other; you’d meet up in Los Angeles. And then you’d get the East L.A. kids. You’d get the South L.A. kids. We all came together from different parts of Los Angeles to party at these events, and I loved that it had that diversity. I would have never gone to East L.A. if it weren’t for undergrounds. I would not really know much about it, or go to South Central. I would never get to experience these types of neighborhoods.”

“There were people coming from upper- and middle-class neighborhoods, connecting with breakdancing music and freestyle,” says Adachi of the era. “There were people from lower incomes connecting. You weren’t there because you thought it was the cool thing; you really had to like the music. There were people there who were into computers, like programmers. There were lots of musicians, sound engineering students, fashion people, a lot of people interested in the next level of technology, music and art.”

“It was people’s lives,” says Rotella. “They didn’t like any other type of music. They didn’t go to any other kinds of events. They were hardcore. The people that were behind the scenes, it was do-it-yourself, just like punk rock. They had to do it themselves to make it happen. And society was against you. You were an outcast. You were not accepted.”

Frank Acevedo, who has co-owned the space on Cesar E. Chavez for more than a decade, was heavily involved with the ‘90s rave scene himself. As a teen, he worked for old-school promoters like Daven “The Madhatter” Michaels and Tef Foo.

“Growing up in Rampart and MacArthur Park, what was happening all around me was the beginning of these violent street gangs,” he says. “I didn’t want to have any part of it, and the easiest thing for me to do was to participate in this alternative movement—which may have saved my life.”

Acevedo and his team are currently reinventing the space, reopening this year as the Boyle Heights Arts Conservatory for kids. It will include classes on electronic music, Ableton Live and DJing.

“I would love to have some kind of reunion—an anniversary kind of thing at the venue,” says Acevedo. “We’re trying to get the next generation involved with electronic music, to take it forward.”

Back west across the river, the city’s heart is pulsing with money and a cultural renaissance that is turning heads across the country. Last year, GQ dubbed Downtown Los Angeles as “America’s Next Great City.”

But the rave scene was decades ahead, making noise and attracting spirits to its nocturnal wonders long before downtown was cool. You can still feel the vibrations, and the afterimages remain, providing inspiration for the next wave of rebels and dreamers and dancers.

Photos by Beau McGavin, James Warner and Ray Klein