How One Company is Using Dance Culture to Fight Mental Health Issues

Until very recently, the electronic music scene suffered its mental health issues in silence. The never-ending party and projection of unbridled, unchecked hedonism looks from the outside like the picture of a life lived in a state of carefree bliss. But the comedown—be it drug-induced or otherwise—is rarely discussed publicly, and the awkward silence surrounding the physical and mental health of our scene needs a consistent discourse.

DJs like Prosumer, Benga, and Erick Morillo spoke out last year about their depressive episodes, while veritable EDM megastar Avicii called time on his hugely lucrative touring career at its peak, citing physical and mental burnout. The lifestyle of the perpetual tour has left many artists struggling with mental health problems through lack of sleep, ill health, substance abuse issues, and lengthy periods of isolation in hotels and airports.

"Music has a tendency to link to your emotions really strongly, and when you think about your favorite festival or artist or song, chances are you love that because it connected with you on a deeply personal level."

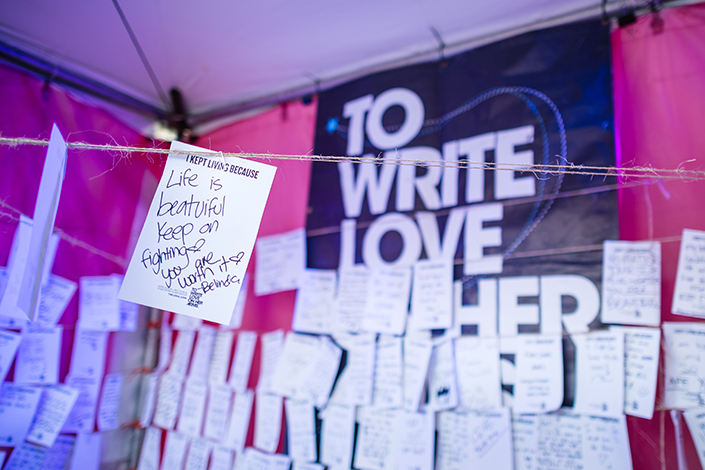

Dance music has a tendency to attract those with issues to confront. Historically, the dancefloor represented a safe haven for the oppressed and marginalized, many of whom are susceptible to depression and substance abuse. While it will continue to provide sanctuary to those bruised souls, we could be doing a better job of encouraging our community to engage with itself and care for one another, beyond making sure we’re safe in that moment.

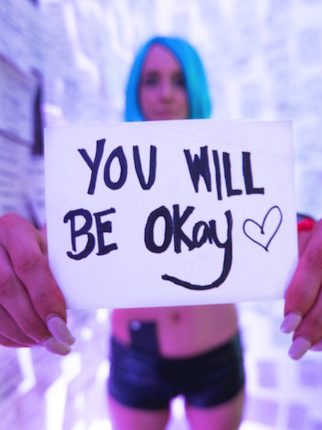

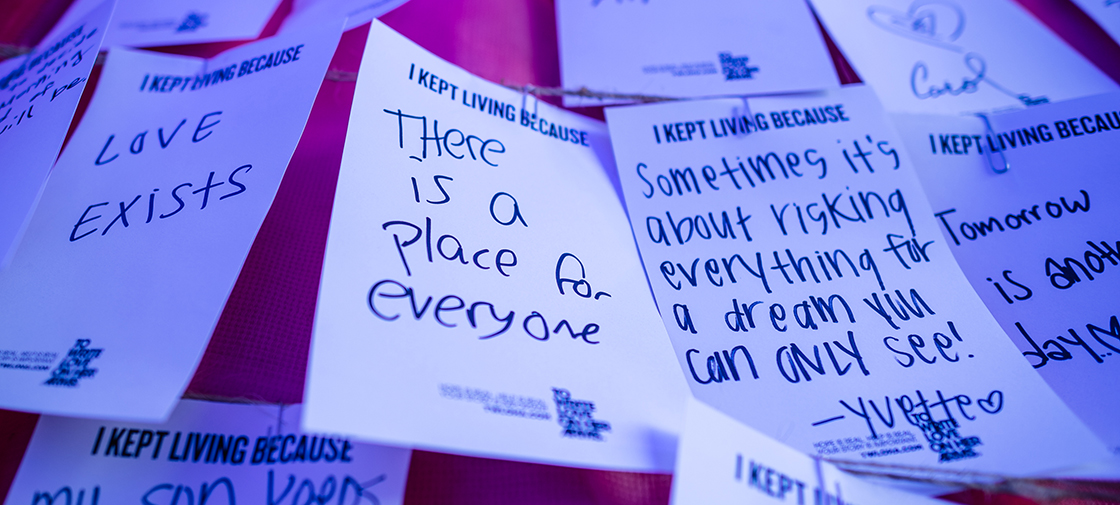

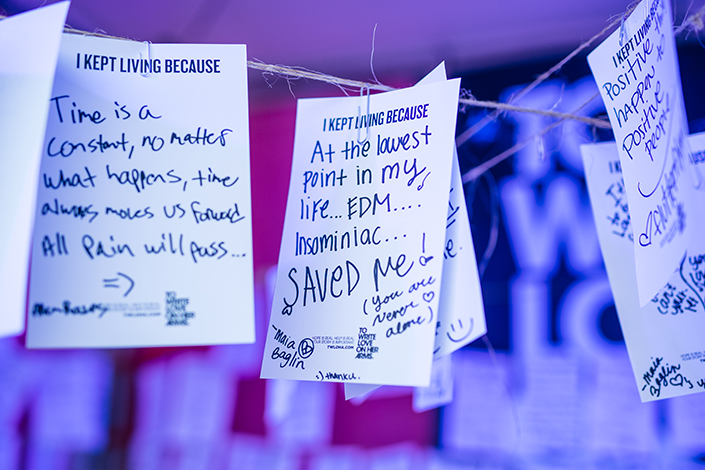

To raise awareness about depression within our community, Insomniac has partnered up with To Write Love on Her Arms, a nonprofit organization aimed at helping those struggling with depression, self-injury, addiction and suicidal tendencies. As avid festivalgoers, TWLOHA staunchly believe in the power of music and the collective support of the dancefloor as a crucial part of recovery. Writer and sometimes dancefloor miserabilist Ross Gardiner chatted with Chad Moses—TWLOHA’s leader in festival outreach—over the phone from his home in Florida, as he battened down the hatches in anticipation of Hurricane Irma.

How are preparations going, Chad? Are you getting out soon?!

It’s nuts, dude. We’ve done all the preparation we need to: remove all the patio furniture and loose articles, board up your windows, stockpiling water. It’s like preparing for a zombie apocalypse!

I often wonder about the support that comes after natural disasters like this, and how the aid is always physical: water, food, shelter, etcetera. There doesn’t seem to ever be any talk of mental or emotional support for victims of extreme weather.

People don’t really think about the aftercare of anxiety or coping with loss that comes after something like a hurricane. If I broke my arm during the storm, people would see that, and they would implore me to get support—but would they do the same if I were suffering from anxiety or PTSD?

At the end of the day, if my aim is to be physically safe, I have to approach this from a more holistic standpoint. I need to make sure that I am mentally strong when I’m tending to my physical well-being. I think as we tend to the obvious physical damage that will occur, we have to be attuned to the mental and emotional demands, too.

It seems like the cathartic effect of music is an important element of To Write Love on Her Arms’ ethos. Can you tell me a little about that?

Absolutely, man. “Catharsis” is certainly the word. In order for something to really be cathartic, you have to be attuned to the present and to what is lacking in your life. Music has a tendency to link to your emotions really strongly, and when you think about your favorite festival or artist or song, chances are you love that because it connected with you on a deeply personal level.

Music festivals, for me, are very powerful in that sense. You have this sea of humanity—all of these people are there searching for something—whether it’s just a good time or perhaps some kind of release. You can dance, sing, meet new people, and really open yourself up to those around you in a way you might not be able to in the real world. That’s super important for helping people out of emotional isolation.

Electronic music particularly has used the dancefloor as its safe space, and when you go to a proper club or dance festival anywhere, you’ll see people wiping their feet at the edge of the floor and dancing their troubles away. It’s extremely powerful.

I grew to notice that when I started going to more EDM shows. I found myself dancing in the middle of the crowd, and I saw lots of people looking around at one another, dancing with one another, not really looking at the DJ. I realized that the experience wasn’t watching an act live, as much as it was dancing with people. The sense of community is a lot stronger in the dance scene than any other I’ve experienced, I think.

I don’t think we can really have a conversation about mental health in dance music without talking about drugs. The conversation about MDMA use typically revolves around the risk of physical harm or death, but its long-term and short-term mental effects—anxiety, paranoia, disturbed sleep, I could go on—are rarely discussed. How do you see this connection?

There’s obviously a connection there between dance music and drug use, and I think that plays into your previous point about the dancefloor being a sanctuary of sorts for people perhaps on the outskirts of society. There’s obviously going to be people drawn to the scene by the drugs, and some drawn by the music and the culture. But it’s very important that there are support networks in place for people that are in recovery but still need the catharsis of the dancefloor. And I think through the Consciousness Group, Insomniac has always been super progressive about helping people with a history of substance abuse find a new place within the scene.

Here’s another point: You see people at festivals, and they’re maybe having the best weekend of their year. But by Wednesday, they might be coming down, sleep-deprived, serotonin has bottomed out. How do we reach people with support in that moment, away from the festival?

I think this has to be actioned by a fundamental shift in our culture around discussing mental problems. I think people need to become better at asking questions, and in being more patient in waiting for the answers to unfold.

The onus is on us as concerned community members to engage with one another after the festival and to keep the conversation going. Like I said, this process of dealing with mental health problems requires patience, and there isn’t a quick fix. If you notice that one of your friends seems to be having a difficult time at a festival, for whatever reason, you should be making the effort to let that person know you’re there and ready to talk if they need to.

I wish there was a formula to address some of the darker aspects to our culture, but I honestly think the only meaningful change we’re going to see is from people caring for other people on an individual level and on a cultural level.

So, if I think one of my friends is going through a dark patch, but I’m not really sure how to address it, where should I begin the conversation?

Start by simply addressing that concern. Don’t be afraid to tell your friend what you miss about them. My life was changed by the fact that I had one friend say, “Hey, where have you been? I miss your smile. Can you let me know where that smile went?” That was a hard question for her to ask, and it really led to some difficult, heavy conversations.

Using your own story is also hugely valuable. If you have experienced depression, or the value of counseling, you should be open about that. You should share your experiences with your friends to help them feel less alone. It should also be said that suicide prevention hotlines aren’t just there for people in immediate crisis. These are people that can help you understand how you came to this place. If you are having difficulties, and you need to talk to somebody, you can call 1-800-273-TALK. If you don’t feel like talking, you can shoot us a text at 741-741—any time, day or night.

If you’re still not sure about how to frame this conversation, or what questions you should be looking to ask, come visit our website. We’ve got a bunch of resources on there, links to hotlines. You can search for counselors or recovery centers near you.

Follow To Write Love on Her Arms on Facebook | Twitter | Instagram