How to Talk to Your Kids About Dubstep

You may recognize it as the sound that spawned numerous parody YouTube videos, such as “Elders React to Dubstep” and Key and Peele’s comedic take on the genre in their “Dubstep” sketch. But by the time YouTube and mainstream media (in America, at least) started catching on to it, dubstep had morphed considerably from its humble beginnings in a record shop in Croyden, South London. If the only person you can name in the genre is Skrillex circa 2012, you’re in need of some schooling. But don’t worry—this quick crash course will get you up to speed.

Unlike other genres that may not have a clear beginning or end—or may have started simultaneously in multiple locations, with multiple artists and multiple tracks—dubstep has an origin point: Big Apple Records. The Croyden shop also housed a studio, where DJs Artwork and Hijak would mess around with making beats.

The two opened up their workspace to their friends and young, aspiring DJs like Hatcha, who was a kid when he first started hanging out at Big Apple. He got decks and practiced nonstop, and soon he was making his own sounds and developing his own unique taste (Big Apple eventually hired him on as a buyer).

“Like any great underground movement, what dubstep was really born out of was boredom.”

Between 1999 and 2002, dubstep pioneers like Skream, Benga, Coki, Mala, Benny Ill, and Loefah were hanging out at the shop regularly. The young producers—especially Skream and Benga—would bring in tracks they were working on for Hatcha to listen to and give his critiques.

Skream and Benga were teenagers at the time, and being young and open-minded to undeveloped sounds meant they were happy to experiment with a darker, slower type of kind-of-but-not-really-garage. In 2003, they released “The Judgement,” a growling track that eschewed not only the traditional verse-chorus-verse format of your standard pop song but also the dance music standard of regularly timed kick drums and percussion.

By that time, Hatcha was playing dark grime and proto-dubstep sets at FWD>>, the South London party created by Tempa Recordings label cofounder Sarah Lockhart. It wasn’t until 2003 that fed-up garage fans looking for a new sound and a less pretentious scene found what they craved at FWD>> parties. Hatcha started playing dubstep there regularly, dropping tracks by the Big Apple kids. He also played the infant genre on his own show on Rinse FM, which grew to be the UK’s biggest pirate radio station (and one of the biggest purveyors of the dubstep sound) between 2003 and 2005.

Like any great underground movement, what dubstep was really born out of was boredom. By the early 2000s, drum & bass was all starting to sound the same. Meanwhile, 2-step and garage, the genres born out of D&B, were too much of a scene, with the clientele mostly consisting of tracksuit-clad gangsters arriving in limos and ordering bottle service.

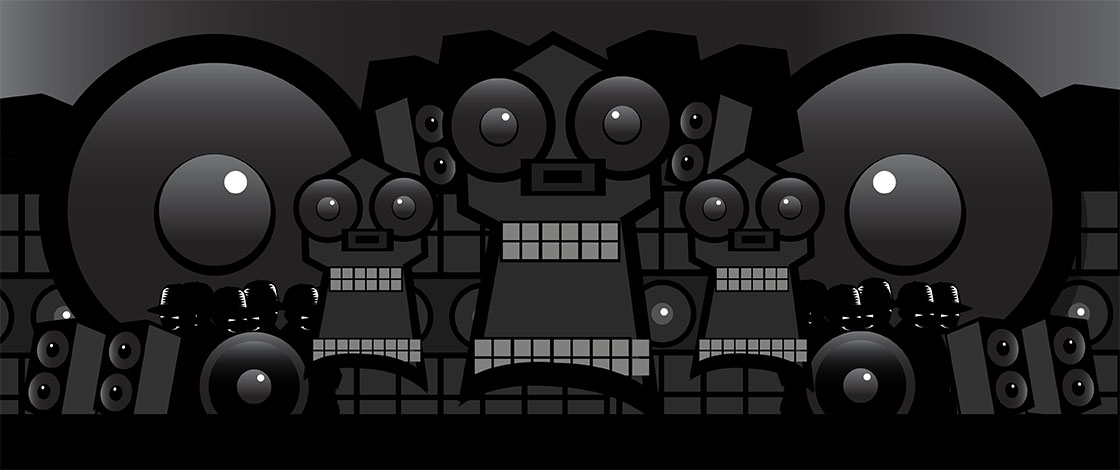

Dubstep was a departure from its predecessors because it wasn’t afraid of having bass be extra dark and loud, but also because the space between beats was just as important as the beats themselves. You know that bass that you don’t hear as much as feel? That’s sub-bass, and dubstep’s all about it.

That sub-bass takes you to another level when you hear it, the vibrations shaking the building and making your face melt, your dancing a combination of jerking motions and slow sways. This is 140 BPM but it feels like 70, and for those that love it, it’s glue. They get stuck in it—stuck in that moment before the drop, with the snare hitting every half beat and the sub-bass-induced pulsations making it hard for you to see. That’s the kind of moody, minimalist dubstep that started it all.

There’s a lot more history we could delve into—you can’t fully dissect dubstep’s beginnings without also touching on its parent genre, drum & bass, and the dub music that was coming out of Jamaica’s innovative soundsystem parties—but that’s a lesson for upperclassmen, and we’re at dubstep 101.

Compared to the 10-year rise of D&B, dubstep grew up fast. That’s partially because dubstep came of age alongside the internet and some of the first easily accessible digital audio workstations (DAWs), Reason and Fruity Loops. The latter development meant that anyone who could get their hands on the software could try making a tune—gone were the days of needing thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment to DJ. If DAWs were the tinder, though, the internet was the match. South London may have been the epicenter of dubstep, but anyone in the world could follow along online.

The genre quickly exploded worldwide. In 2005, Dubstep Forum started as an online space for fans of the genre to share opinions and favorite tracks. It grew from a few hundred users to over 20,000 by the end of 2006. At the end of that same year, BBC Radio 1 host Mary Anne Hobbs started a radio show called Dubstep Warz. She featured a new record from Skream—“Midnight Request Line,” a more melodic take on dubstep that showed how the genre could evolve and blend into something with mainstream potential.

By then, dubstep wasn’t just concentrated in London anymore, though the original players were still promoting the sound. In 2008, Benga and Coki released “Night,” a track that showed how far the genre had come. Unlike “The Judgement,” which still attempted to fill the empty space of a song with percussion and other elements, “Night” left room for the sub-bass to expand, using minimal percussion and a simple lead. Dubstep seemed to have found its footing, but as soon as it was set in its self-discovery, things began to change.

After Dubstep Warz aired, Americans finally started paying attention to dubstep. The show was on from 2–4am in London, which meant it played in the afternoon in the US.

Some of the earliest adopters of the genre in the States were Joe Nice, who started throwing America’s first dubstep parties (and holds the nickname “America’s Dubstep Ambassador”), and the crew behind Smog Records (Drew Best, Danny Johnson, and dubstep producer 12th Planet), which started throwing dubstep parties in 2006. These parties were attended by a young Skrillex, who, with Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites, was catapulted to mainstream success, winning three Grammys in 2012. His was a mixture of genres and a sort of evolution (or devolution, depending on whom you ask) of dubstep: brostep.

Dubstep purists will say brostep sucks—it’s just drop after heavy drop, a total departure from the spread-out drops of OG dubstep, when DJs led with sub-bass and followed up, intermittently, with percussion. Whether you love it or hate it, though, the rise of brostep in America and across the globe was definitely a continuation of the dubstep sound—another step in the staircase toward bass music, the current name for any track with a focus on killer bass. What we call dubstep now might sound different from the dubstep that came out of Big Apple Records in the 2000s, but the way bass music is evolving is the same. With the rise in subgenres like future bass, trap, jungle terror, and vomit step—and the increasing fame of genre-bending bass music artists like Flume, Mura Masa, and Cashmere Cat—it’s clear that fans of bass can always count on bass producers to keep the scene from getting stale. Luckily, some things never change.