Rabbit Moons, Violet Dawns and the Call of the Desert

The desert is beautiful and deadly, the untamed home of outcasts and rebels. At night, as the rabbit in the moon jumps saguaros and Joshua trees, it can make hearts glow. It’s where dreamers, loners and anarchists end up when all other options run dry. Whether we’re talking about cowboys, Bedouins, Luke Skywalker on Tatooine, the gangster Bugsy Siegel on the Las Vegas Strip, or the techno Dadaists behind Burning Man at Black Rock City, the desert is where civilization transforms before our eyes: The future vibrates like a mirage on its horizon, warning us that heat, bones and thirst stand in the way of our search.

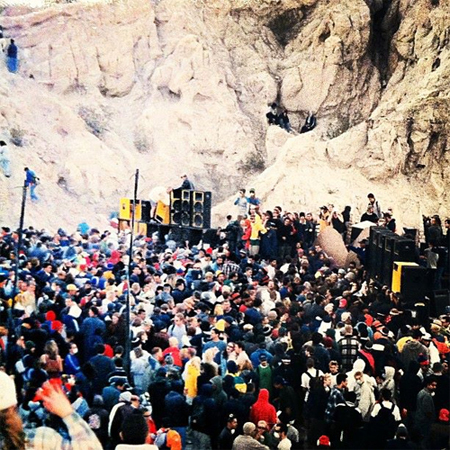

It didn’t take long before the San Francisco and Los Angeles rave scenes merged with the Black Rock City ethos.

When it comes to the history of EDM, the desert has become one of our most native habitats. Water-soaked cities like New York, Chicago and Detroit birthed modern dance music. London, Manchester, Berlin, Amsterdam, Rome—and more recently, Paris, Stockholm and Montreal—have fed us many streams of techno, house, ambient, drum & bass, dubstep, and so on from their cosmopolitan rivers. But it was from the sprawling desert cities of the West that rave culture finally boomeranged into world dominance.

In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Hunter S. Thompson’s 1971 book about the post-’60s flower-child comedown, protagonist Raoul Duke—memorably played by Johnny Depp in Terry Gilliam’s 1998 film adaptation—reflects on the spiritual clarity of the Nevada desert: “San Francisco in the middle ’60s was a very special time and place to be a part of,” he famously says. “We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave … So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look west, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.”

At the bottom of every ocean is a desert, and Thompson’s Duke imbibes many drugs to reach its swelling waves. He never catches them. His answer instead would come in the late ’80s with rave’s romance of the microchip—something Thompson might surely have feared and loathed. Other counterculture prophets—like Timothy Leary and Terrence McKenna—embraced it, frequenting raves all along the West Coast in the ’90s. While Duke looked back from the desert at the heady days of San Francisco’s Summer of Love, youths 30 years later were looking onward to the stars and the moon, more Star Wars than Easy Rider.

At the bottom of every ocean is a desert, and Thompson’s Duke imbibes many drugs to reach its swelling waves. He never catches them. His answer instead would come in the late ’80s with rave’s romance of the microchip—something Thompson might surely have feared and loathed. Other counterculture prophets—like Timothy Leary and Terrence McKenna—embraced it, frequenting raves all along the West Coast in the ’90s. While Duke looked back from the desert at the heady days of San Francisco’s Summer of Love, youths 30 years later were looking onward to the stars and the moon, more Star Wars than Easy Rider.

It’s as if Duke’s hallucination turned out to be true, an overlaid matrix of the virtual and the real gleaming under the hot desert sun. Computer technology—and the creative energy it unleashed—kept pulsing as culture jammers in 1990 re-established Burning Man in the Nevada desert, after its first incarnation was banned from San Francisco’s Baker Beach. It didn’t take long before the San Francisco and Los Angeles rave scenes merged with the Black Rock City ethos outside Reno, helping to supply its growing numbers and its hyperreal Mad Max soundtrack. Duke would no longer need to pine for San Francisco’s “strange memories” because this time, they washed onto his steep hill to a new high-water mark.

In what was a kind of precognitive wish fulfillment, England’s The Orb captured this potential with 1990’s ambient house classic “Little Fluffy Clouds.” It became a dawn anthem in the West—the voice of songwriter Ricky Lee Jones reminiscing about her childhood in the desert—and provided a psychedelic spur to EDM’s ambitious frontier.

“What were the skies like when you were young?” a young man asks. “They went on forever,” Jones answers dreamily. “We lived in Arizona, and the skies always had little fluffy clouds. They were long and clear, and there were lots of stars at night. And when it would rain it would all turn … they were beautiful, the most beautiful skies, as a matter of fact. The sunsets were purple and red and yellow and on fire, and the clouds would catch the colors everywhere.”

As they pulled up, rolled down their window, and said hello, they noticed their saviors were wearing BMX masks and holding M-16 automatic rifles. They quickly sped on.

The Southern California desert rave movement, like Burning Man, first came about because it offered an escape from legal and monetary constraints. The Mojave was a lunar landscape filled with adventures in the unknown: From inside small canyons to dry lake beds to breathtaking lookouts, pioneering rave collective Moontribe helped expand techno’s native imagination. It took risks that were sometimes strange and dangerous. One cofounder a few times got so lost scouting locations that once he almost died of thirst; so he cut open a cactus and sucked on its wet flesh, only to find it filled with hundreds of tiny burs that swelled his tongue. On another occasion, he and his friends needed directions and saw a campfire in a sea of darkness. As they pulled up, rolled down their window, and said hello, they noticed their saviors were wearing BMX masks and holding M-16 automatic rifles. They quickly sped on. Such daring inspired others like Dune, which brought a second wave to discover the action had moved from the city to the sands.

The desert is always out there, on the edge, full of surreal surprises. From Burners on “safari,” hunting stuffed animals with live ammunition, to rumors of stealth fighters flying over a moonlit dancefloor, it’s a canvas for our wildest dreams. Mad Men’s Don Draper encounters that same trippy power in 2008’s “Jet Set” episode when he follows a girl to a Palm Springs retreat, complete with a European viscount at the dinner table. Pee-wee Herman’s desert nightmare of a Cabazon Tyrannosaurus Rex munching on his beloved bicycle in 1985’s Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, remains one of Tim Burton’s starkest images.

But there’s one vision that now stands taller than most and is stranger than fiction: a giant speedway ring in the Nevada desert, glowing in the darkness from across many quiet miles, fireworks bursting overhead, a Ferris wheel cranking ‘round, stages strobing with fire, and a pageant of dream warriors raving before a big Night Owl, his strange eyes flashing. As Insomniac decided to leave Los Angeles and look for a home that welcomed them and allowed them to grow, and the festival ended up in the Las Vegas desert, it was one of the best things that could ever happen for dance music—a stroke of luck.

Because temples belong in desert landscapes: temples to gods, temples to money, temples to art, temples to joy—worship worthy of Pink Floyd’s “Breathe” or Bubble Club’s modern-day classic “Violet Morning Moon.” It’s empty at first glance, daring us to fill in the blanks; knock down some hills and dynamite some canyons, make way for water to pour down aqueducts from glaciers and mountains to cities gasping for water. Los Angeles, Reno, Las Vegas—they’re all sun-stroked civilizations that drink from a dusty straw. The wilder, the better. Run, rabbit, run.