The (Funk) House That Insomniac Built

In the beginning, there was techno.

No, not that kind of techno.

“These funk and soul records are the origin of modern music, and the source of all the samples that you hear in so many different forms of dance music.”

Not the techno you’d hear being played today by artists like Craig Williams or Pilo in a dark club in Downtown L.A. Techno as in dance music. House music. Rave music. In the early-‘90s L.A. underground scene, techno was the catchall term for whatever was pumping out of the main room. But there was the second room—a smaller room— where DJs would spin everything from disco and funk to hip-hop and rock. “A lot of people looked at it like the chill room,” remembers Graham Funke, a frequent DJ at Insomniac events and longtime friend of the company’s founder, Pasquale Rotella. “But it wasn’t really a chill room. It was just a groovier room.”

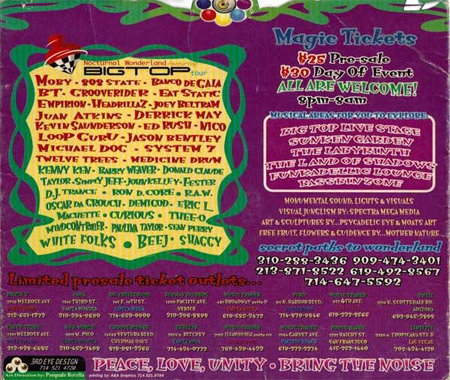

Rotella brought the funk room (dubbed the Funkadelic Lounge) to the festival crowd at a handful of early Nocturnal Wonderland shows, where DJs like Sean “Pimp Daddy” Perry and Mike Messex—and later J-Boogie and Graham Funke—were regulars. But by the early ‘00s, a shift began to occur. Open-format DJing, as it was referred to, became the prominent style in nightclubs across the country. Vegas spots that had previously booked local DJs to play electronica started booking names like Grandmaster Flash, Mark Ronson, DJ AM, Vice and Z-Trip, and it wasn’t long before the open-format sound moved out of the side rooms and into the main room. The last Funkadelic Lounge was hosted at Nocturnal Wonderland 1998. Now it’s back, remixed and reimagined for a new generation of dance music fans as the Funk House, hosted by Planet Rock and featuring the likes of DJ Jazzy Jeff, Z-Trip, Poolside, Melo-D and Rhettmatic of the World Famous Beat Junkies, Soul Clap, Graham Funke and many more.

“The cool thing is that all of us are friends,” says Jazzy Jeff of the artists on the Funk House lineup. “Me and Z-Trip are super duper close, and we do some stuff together, but we really don’t get a chance to see each other play. I think we’re probably more excited than the people coming to see us!”

“It’s always hard for us to find exactly where we fit on festival lineups,” admits Charlie Levine from Soul Clap. “They’ll have a more commercial stage, but even the more underground stages, we don’t really fit on, either. To have a home to play at a bigger festival is really dope.”

For Jeff, Melo-D and Soul Clap, the Funk House presents the perfect opportunity to spread the original open-format gospel of funk, soul and disco to those who have experienced only the big room EDM sound.

“It’s cool that guys like Tiësto and Steve Aoki are still the main acts being highlighted at these events, because in my eyes, they’ve been producing dance music for as long as we’ve been doing hip-hop and turntablism,” says Melo-D. “They deserve their shine, but at the same time, there’s really no balance left anymore. [The Funk House] is a good way to educate the younger kids that may be looking for a new sound, and I’m excited to be a part of it.”

“We grew up with the funk,” says Soul Clap’s Eli Goldstein. “Charlie was actually George Clinton in a Parliament cover band in summer camp, so this is just a big part of who we are. These funk and soul records are the origin of modern music, and the source of all the samples that you hear in so many different forms of dance music.”

Programming the Funk House with newcomers and established selectors was most definitely by design, and the eclectic nature of the lineup should make for an anything-goes atmosphere. It could also potentially be the one stage where the fans have the most direct impact on what gets played.

“My brain is always going through a thousand scenarios,” says Jeff. “Who’s playing, how long have people been out there, is there a style that has been missed? I’m always thinking about that kind of stuff, because I want to make sure I add something a little bit different than everybody else to make the night complete.”

“Open format is not a style of DJing, it is DJing. It’s the foundation of DJing. This is what’s getting deposited into Beyond Wonderland.”

“When we play at a big festival with the younger kids, we bring in the classics and try to educate, now more than ever,” says Eli. “This divide with EDM not being as connected to the history of the culture and the history of the music… It should be all DJs’ jobs, old-school ones and anybody that has respect for the culture, to educate in all their sets.”

No doubt old-school heads who remember the Funkadelic Lounge will be excited for its rebirth, but the real test will be how many new-school ravers will be drawn to the multifarious transmissions emanating from the speakers. Constructed in a centralized location between Beyond’s two largest stages, the Funk House is prime real estate. Graham Funke, for one, is hoping that bridge isn’t just a literal one but a metaphoric one.

“If you look at the guys who developed DJing—Kool Herc, Bambaataa, Flash, those guys—they were playing open format,” says Graham Funke. “They played a rock song, a funk song, a very limited number of hip-hop songs; they played all this stuff at their gigs. Open format is not a style of DJing, it is DJing. It’s the foundation of DJing. This is what’s getting deposited into Beyond Wonderland—the very foundation of what this culture is. This is the perfect time to reinsert the funk room into the festival circuit. Pasquale’s vision is finally manifesting.”

“It felt like the right time to mix things up and bring more soul into the culture,” says Rotella. “Besides, I personally miss it. The vibe in those funk rooms was always happy and feel-good, and you can never have enough of that.”