Can EDM Survive at Dial-up Speeds?

The debate over net neutrality flared up again this week, with Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler proposing what are being called the strongest net neutrality measures ever.

In an op-ed in Wired published February 4, 2015, Wheeler writes:

Originally, I believed that the FCC could assure internet openness through a determination of “commercial reasonableness” under Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. While a recent court decision seemed to draw a roadmap for using this approach, I became concerned that this relatively new concept might, down the road, be interpreted to mean what is reasonable for commercial interests, not consumers.

That is why I am proposing that the FCC use its Title II authority to implement and enforce open internet protections.

Using this authority, I am submitting to my colleagues the strongest open internet protections ever proposed by the FCC. These enforceable, bright-line rules will ban paid prioritization, and the blocking and throttling of lawful content and services. I propose to fully apply—for the first time ever—those bright-line rules to mobile broadband. My proposal assures the rights of internet users to go where they want, when they want, and the rights of innovators to introduce new products without asking anyone’s permission.

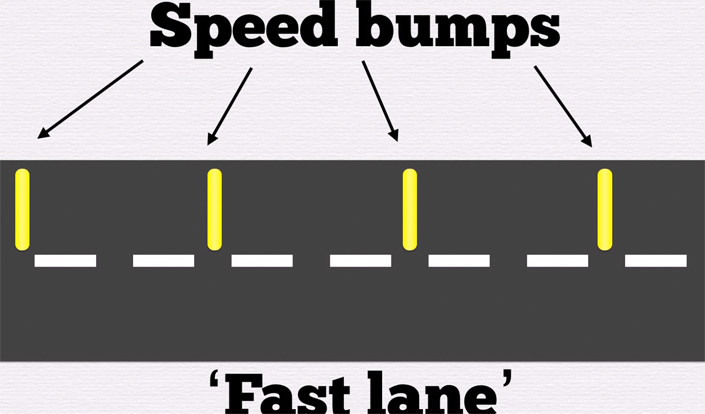

Wheeler’s announcement comes after 4 million public comments were made in regard to keeping the internet free from paid prioritization, which would essentially slow down the web for those unwilling or unable to pay more for “fast lanes.” While the final outcome won’t be clear until Wheeler releases his full proposal and the FCC votes on net neutrality measures later this month, his announcement is being heralded as a huge win for the maintenace of an equal internet for all.

Power to the people.

This original article appeared on September 9, 2014:

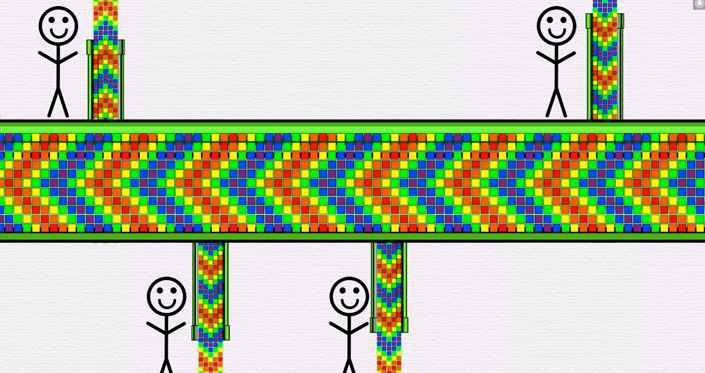

When Sonny Moore was 13 years old, he used high-speed internet to download a program called FL Studio, typically referred to as FruityLoops. He used the internet to create and distribute his music. He then became Skrillex. The internet has revolutionized music, especially electronic music, by creating an equal playing field for creation and distribution. Without it, Skrillex would likely still be just Sonny.

But thanks to the FCC’s failure to protect the internet, a service the UN called a “human right,” the net as we know it may soon function differently, which would have major repercussions for EDM.

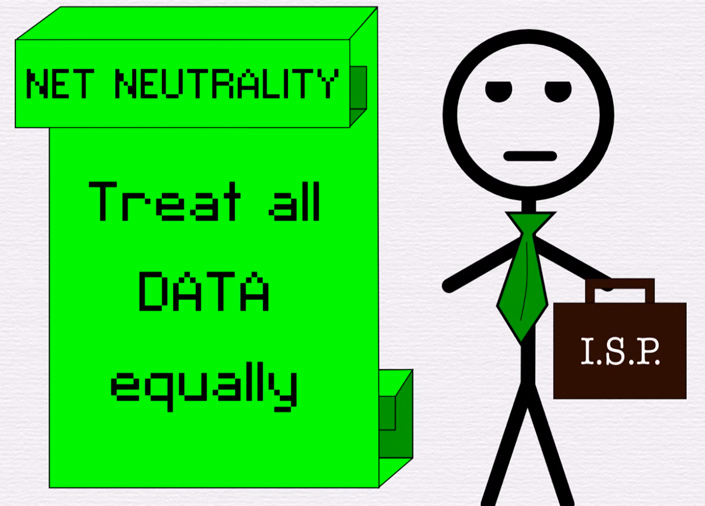

The main issue is called “paid prioritization.” For years, you’ve been paying for equal access to broadband (and before that, dial-up) without discrimination of content. Internet service providers (ISPs), which include Verizon and Comcast, provide that access. When you visit an underground EDM blog like Basshaus, you do so at the same internet speed as when you’re streaming on Spotify. The internet doesn’t have tiers. SoundCloud can’t negotiate a deal with Comcast for faster internet speeds than Gorilla vs. Bear, giving them a competitive advantage. This is called “net neutrality.”

If ISPs prioritize the internet into a tiered system, the web could slow down for a large number of musicians, streaming services, and those who can’t afford to pay-to-play.

The FCC’s open internet rules protected net neutrality. In January, however, the rules the FCC had established in 2010 requiring ISPs to treat all internet traffic equally were thrown out by a US appeals court, following a lawsuit by Verizon.

Without a level playing field for content to be broadcasted without discrimination, musicians may no longer have the great equalizer to express themselves: a free internet. If net neutrality is compromised, the same freedoms that allowed Skrillex and deadmau5 to build a following will be eroded.

Slowing internet speeds is something ISPs have done before, especially when doing so serves their agenda. Level 3, a company that helps ISPs connect to the net, in May accused six unnamed ISPs of “deliberately harming the service they deliver to their paying customers.” Why would the ISP deliberately slow down a customer’s connection? Well, it would allow the ISPs to charge Level 3 for the heavy traffic caused by a site like Netflix. It would also allow the ISPs to ask Netflix for a paid peering deal, i.e., access to faster internet. As a result, Netflix agreed to peering deals with Comcast in February and Verizon in May, as customers had been complaining about the bad streaming quality.

Such intentional slowing of internet speeds is called “throttling,” and it’s just the beginning. With the FCC’s proposed “fast lane,” the ISPs could have permission to openly charge blogs, upstart streaming services and musicians for priority access to the net. Verizon has been aggressively vocal about their right to prioritize:

“Such flexibility to experiment with alternative arrangements not only can reduce costs to end-users while allowing them to access the content they demand,” wrote Verizon in a statement to the FCC, “but also benefit and spur continued investment in broadband infrastructure.”

In other words, Verizon wants the flexibility to profit from providing various service packages. What this means is that, if ISPs prioritize the internet into a tiered system, the web could slow down for a large number of musicians, streaming services, and those who can’t afford to “pay-to-play.” And for now, ISPs have the law on their side.

In May, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler proposed an alternative to mitigate the January decision to void the FCC’s open internet rules, suggesting a “fast lane” for companies willing to pay for access. On July 15, this alternative was lambasted by Netflix in a 28-page filing. “No rules would be better than rules legalizing discrimination on the Internet,” wrote Netflix, who also accused Comcast of seeking a pay-for-play deal from the company, slowing down their streaming from HD to “nearly VHS quality.” At bayonet point, Netflix negotiated the aforementioned peering deals with Comcast and Verizon for faster internet.

“You can expect more of this in the future,” says Kevin Erickson, a representative of the Future of Music Coalition, a nonprofit group representing musicians who advocate for net neutrality.

Netflix, of course, has the resources to gain the competitive advantage. But what about a DJ who has yet to break out?

“The court decision overturning the open internet order could inhibit competition and restrict your choices as an artist and fan,” says Erickson. “If you’re an artist that thinks Spotify is a bad deal for artists, for example, and you’d prefer to have your music available on SoundCloud or Beatport instead, an ISP can decide that Spotify can pay more and thus interfere with your music getting to fans on your preferred platform.”

And if you think a company like Comcast (who may soon merge with Time Warner) won’t be rigging the system to benefit their own music and video streaming agenda, think again. In 2007, when Comcast subscribers were trying to access peer-to-peer applications like BitTorrent, the ISP just slowed down the internet for consumers. (The FCC forced Comcast to stop this practice of content discrimination and, in some cases, to stop monitoring the online habits of customers.)

And what motivated Comcast to interfere with their customers’ internet usage? Pure capitalism. “BitTorrent and similar applications,” as noted in a report by InformationWeek, “allow Internet users to view video that would cost them money through cable providers, including Comcast.”

Electronic music, which is born and distributed almost exclusively on the internet, is being threatened in a similar manner. Look at the recent T-Mobile UnCarrier 6.0 deal, which includes partnerships with Spotify, Pandora, iTunes Radio, Slacker, iHeartRadio, Milk Music, and Rhapsody. These partnerships, T-Mobile says, allow for streaming that will not count against a customer’s data caps on mobile streaming. Upstart streaming apps, however, won’t be included in the deal as it currently stands.

While T-Mobile has said that they will add services based on feedback from customers, this sort of deal limits opportunities for indie artists and upstart streaming services. It’s rigging the system for a handful of bigger players to flourish, while smaller entities are left behind. It’s setting a precedent for ISPs and carriers to create packages benefitting established music streaming services, while reducing opportunities for innovation. As a result, the internet could become more like cable television. And when was the last time you saw an upstart TV network or indie filmmaker included in the channel lineup of, say, Charter Communications?

“The T-Mobile deal gives us a lot to be concerned about because it amounts to T-Mobile picking winners and losers, rather than having services compete to better serve the various needs of different kinds of musicians and fans,” Erickson explains. “Even if they’re not charging services to bypass the data caps, yet, it still undermines net neutrality principles.”

The FCC is also a problem. In 2002, the FCC voted to classify internet access as an ”information service,” meaning it would be unregulated. The goal was to spur investment in ISPs, but in January, the classification essentially led to the dismantling of net neutrality. “Ten years ago, the FCC deregulated these actors. And it can’t now simultaneously pretend to regulate them,” said Susan Crawford, a Harvard Law Professor and advocate of net neutrality, during a January interview with re/code. It’s that sort of inconsistency that led to the courts voiding the FCC’s open internet rules in January.

Now, a broad coalition of media and cultural groups, including Americans for the Arts, Performing Arts Alliance, the League of American Orchestras, Future of Music Coalition and even Netflix, are stepping up the pressure on the FCC to preserve the original intent of the internet. This coalition hopes to convince the FCC to reclassify the internet as a “telecommunications service,” known as Title II, which will allow it to be regulated and protected—keeping the ISPs at bay.

House Republicans and corporate lobbyists, however, seem more interested in profit than freedom of expression. Rep. Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee, a Republican, sees protecting net neutrality as nothing more than a “socialistic proposal.”

“If there’s money to be made in controlling access,” Erickson tells us, “[the ISPs] will certainly try to get that money, and standing between artists and audiences is one way to do that.”

With all the talk of SoundCloud cutting licensing deals with major record labels to avoid copyright litigation, the ways consumers listen to music, and the way musicians share it, are changing rapidly. As of today, the FCC has received over 1.1 million comments (nearly crashing their system), most of which are in support of net neutrality and unhappy with the FCC’s proposed alternative, which would turn the lights out on millions of electronic music composers freely innovating on the internet.

As a result of the surge on their website, the FCC extended the deadline to submit reply comments from September 10 to September 15. They’ve now decided to hold a series of open internet roundtable discussions in September and October, which will be open to the public and can be streamed live here.

The music community has been vocal as well. A consortium of musicians including R.E.M., OK Go, and Merrill Garbus of tUnE-yArDs, filed a statement to the FCC that seems to echo what most musicians think: “We music people know payola when we see it. And what we see in Chairman Wheeler’s proposal doesn’t give us any confidence that we won’t end up with an Internet where pay-by-play rules the day. We’ve heard this song before, and we’re frankly pretty tired of it.”

Most of the public comments to the FCC, however, have been less diplomatic: 7,817 uses of the word “f–k” appeared in comments relating to the FCC’s proposed alternative. Not since the infamous Janet Jackson “wardrobe malfunction” at the 2004 Super Bowl has the agency been flooded in this manner.

Whether the pressure will force the FCC to protect net neutrality is hard to predict. The New York Times and others are urging the FCC to reclassify broadband under Title II of the Communications Act—which would essentially ban paid prioritization. It’s a move that Republicans and ISPs, those who favor deregulation and “free market capitalism,” are fighting to squash.

But unless the FCC steps up in favor of regulation, the outcome won’t be good for artists that aren’t signed to major labels. They simply won’t be able to compete or innovate on a level playing field anymore. Once again, the artistic community will suffer in favor of Wall Street, unless the FCC is compelled to act in favor of net neutrality.