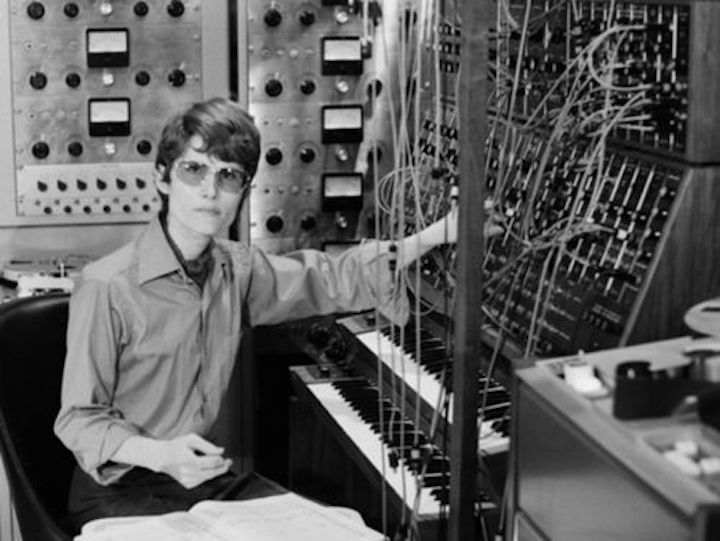

Wendy Carlos: Switched on, Synthed Out

In honor of Women’s History Month, we are throwing some shine on the most influential female industry figures who helped pioneer electronic and dance culture.

Wendy Carlos is among the most fascinating people alive and one of the most distinct voices in electronic music history. She has remained rather private, and you’ll find little of her music via (legitimate) online portals. Yet “nobody is in her league,” said synth guru Robert Moog about Carlos’ skill as a composer and overall pioneer of synthesized music—which of course, once upon a time, was not the ubiquitous, easily accessible phenomenon it is today.

You could even go so far as to say Carlos is one of the key figures in helping make electronic music mainstream—for better or worse (she has expressed more of the latter in several of her rather rare interviews)—via everything from films and video games, to the club and the experimental vanguard, to everywhere in between. Her fingerprints are on everything in the last 50 years, and she’s somewhere on the short list of the 20th century’s most important contributors to the arts.

A Rhode Island native and an intellectual at heart, Carlos had a proclivity for the sciences and studied physics and music while at Brown University, before eventually focusing entirely on music: composition, performance, engineering, recording—you name it. Then Carlos met Bob Moog, inventor of the eponymous Moog, the first commercially available modular synth (it was still around $20K in ‘60s money, though!), which was as memorable as it was difficult to use.

“Bob looked tired but friendly, and we chatted briefly, traded phone numbers and addresses,” recalled Carlos. “It didn’t take long to establish a budding friendship. It was a perfect fit. He was a creative engineer who spoke music; I was a musician who spoke science. It felt like a meeting of simpatico minds, like he were my older brother, perhaps.” And she helped shape what is arguably the instrument that ushered in the era of synthesizer dominance, as it usurped the classical piano and guitar.

Carlos rose to fame for Switched-on Bach, an album she produced, which was entirely electronic covers of Bach. It was the first classical LP to go platinum. Throughout the ‘70s, she stayed busy working on all sorts of classical and more avant garde projects, experimenting with the possibilities of timbre and tuning, and in doing so, created a distinct but also ever-changing sonic signature.

Carlos feels partially responsible for synth catching on via disco, but—not being a fan of looping, monotonous music—she laments her role in the whole thing.

She later further cemented her status in pop culture history for her soundtrack work for Stanley Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. Carlos created much more music for the film than the director ended up using, and after his cuts on The Shining, she vowed never to work with him again. Yet her music accompanies the openings, and sets the tone, for what may continue to be two of the most-viewed films of all time.

Between the releases of those two films, she also became one of—if not the—most visible people in our culture who came out as transgender in the late ‘70s. “The public turned out to be amazingly tolerant—or if you wish, indifferent,” said Carlos.

One thing the 1970s American public was quite certain about was its love of disco. And Carlos feels partially responsible for synth catching on via the genre, but—not being a fan of looping, monotonous music—she laments her role in the whole thing. Carlos told Playboy in a lengthy and revealing interview in 1979:

The synthesizer became well known when advertisers used it to sell products on TV, such as the commercials for ailing cars and the cat sounds to advertise cat food. Pop artists such as Keith Emerson used it rather flamboyantly. Emerson, Lake and Palmer were among the first pop groups to play with it. In Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the sounds came from a synthesizer. And it’s the background on almost every Donna Summer record… It’s nice to know that it’s used on disco, but it would have been healthier for the industry had it not been.

She would go on in the same interview to call out dance music and herself for being an old crank:

If you’re asking me to name the hit disco singles, I can’t, since I generally flee from anything that repeats the same sequence more than 16 times. I mean, if somebody wants to say, “Once upon a time, once upon a time,” I’ve got it after the fourth time. Let us not confuse it with music. But now I sound scholarly and tight-assed and pompous and—fuck it all. This may sound like sour grapes, but I’m putting down almost all of the records that have used the synthesizer this past decade.

So, why is she so influential, even if she isn’t a fan of disco and nightclubbing? Her attention to detail, as far as sounds and music theory and her sort of endless experimentation, are some of the defining elements of her legacy and working methods. You can see her influence in artists from Aphex Twin and Terre Thaemlitz to the more baroque-leaning EDM and pop producers out there, and she’s been sampled by everyone from the Prodigy to Three 6 Mafia. She even collaborated with “Weird Al” Yankovic on a Peter and the Wolf satire.

Beyond anything musical, Carlos has just been a fascinating human all around. From journeys to places like Siberia and Australia, she “acquired a reputation as a leading eclipse photographer.” Her love of the moon has spilled into her music, like on her Moonscapes suite, conceptually designed around the “major moons of the solar system.”

All told, Carlos and her work are indispensable, even if we’ll never agree about disco.